The Power of Communication in Effective Business Change

How to support clear signals amid the stormy weather of transformation

Moments of transformation in business or society often arrive cloaked in tension. It can be a time of heightened uncertainty; it can feel like navigating stormy weather. Expectations shift, structures realign, and long-held routines face disruption. Yet if we are to succeed amid all this flux, one element remains central to navigating complexity: communication. Without it, even the best strategies will crumble under confusion, resistance, or just inertia.

As change is essentially people-driven, communication becomes the vital force behind it. Without clear communication during such times, we risk being exposed to potentially more damage than we expected at the start of a change journey.

The Role of Communication in Change

Transformation, by nature, alters the status quo. If everything stayed the same, nothing would change. Yet the world around us is changing. In business, change is not just a strategic shift for staff, it’s a lived experience that impacts routines, identities, and well-being.

For leaders and managers, communication is the necessary bridge between vision and implementation, between strategy and behaviour. However, communication doesn’t merely mean the transmission of instructions, such as a public safety alert—it frames understanding, aligns incentives, mitigates fears, and creates the emotional and rational buy-in required to move forward.

Recently, I wrote about John Kotter’s 8-Step Change Model, which suggests that successful change depends on building urgency, creating coalitions, developing a vision, and embedding new behaviours into culture. Communication is integral to all eight steps, from igniting the initial urgency to anchoring the change in day-to-day operations.

Yet communication during change should not be just about talking more. It should also be about saying the right things in the right way to the right people at the right time—and listening deeply to feedback.

At its most basic, the well-known transmission model of communication, developed in the 1940s by Claude Shannon and Warren Weaver, helps us understand the mechanics of message delivery:

Sender → Message → Channel → Receiver

It reminds us that clarity, noise, and feedback all matter.

Messages are often disrupted by noise—whether that’s a literal buzz on a call or, more subtly, by fear-driven office gossip that distorts the intended message.

But during a journey of change, this one-way communication model can fall short. It often assumes a passive receiver and underplays the importance of sense-making—how people interpret messages based on values, emotions, context, and concerns for their future. That’s where two-way communication comes in.

In times of change, both modes are essential. The trick is knowing when to use each mode. One-way communication can deliver consistency at scale. Meanwhile, two-way communication helps foster understanding, mitigate resistance, and receive invaluable feedback.

Cognitive Biases: The Human Filters

Since change is usually people-driven, we need to be aware of how human behaviour shapes the way information is received. People don’t take in messages neutrally; we interpret them through mental shortcuts and filters known as cognitive biases, which can distort, resist, or reinforce what’s being said.

Psychologist and Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman describes two modes of thinking that influence how we respond to change: System 1, which is fast, instinctive, and emotional; and System 2, which is slower, more deliberate, and rational. In moments of uncertainty or disruption, most people react first with System 1, emotionally, before System 2 has a chance to kick in. That’s why it's crucial for communicators to speak to emotions before pivoting to logic.

Consider the status quo bias, which makes us favour the current state of affairs, even when it no longer serves us. This bias explains why people often resist change instinctively. Leaders can counter it by presenting clear, compelling reasons why change is necessary, reinforcing what John Kotter calls the need to “create a sense of urgency.”

Then there’s confirmation bias, where we subconsciously seek out information that supports what we already believe. If new messages contradict our assumptions, we often dismiss them. That’s why effective change communication needs to gently challenge existing beliefs and introduce fresh perspectives, especially through trusted, credible voices.

The bandwagon effect, our tendency to follow the majority, can work in favour of change if managed well. This is where Malcolm Gladwell’s Tipping Point comes into play: once a critical mass of people begins to embrace the new way, momentum builds and adoption accelerates. Highlighting stories of early adopters and showcasing progress can help nudge hesitant individuals toward alignment.

Another powerful filter is the negativity bias, where people weigh losses more heavily than equivalent gains. In change settings, this often translates into a fear of what will be lost, even if the benefits are substantial. To overcome this, messages should reframe potential losses as opportunities and highlight tangible, relatable benefits, such as improved collaboration, meaningful incentives, or personal growth.

Other subtle but influential biases can shape how people respond to change. With anchoring, people place undue weight on the first piece of information they hear—so early messages in a transformation can disproportionately influence perceptions. First impressions matter. Availability bias also plays a role: people judge risks or outcomes based on what comes easily to mind. If a previous change initiative failed publicly, that memory may colour their outlook on future efforts, even if the context has shifted.

There’s also the issue of substitution, where instead of answering a hard question like “Is this change strategy effective?”, we unconsciously answer a simpler one like “Does this feel familiar or easy to grasp?”, without realising we’ve swapped the question. And representativeness bias can lead people to draw faulty conclusions based on similarity to past patterns, while ignoring relevant data or probabilities.

Finally, the way information is presented, framing effects, can dramatically influence decision-making. The same outcome can be seen as a gain or a loss depending on how it's framed. Saying “80% success rate” feels very different from saying “20% failure rate,” even though the numbers are identical. This means communicators must choose language carefully, framing change in terms that inspire hope and confidence rather than fear or doubt.

All of these examples remind us that people don’t absorb information as clean slates. We tend to make decisions based only on the information we have in front of us, without realising what we don’t know or what might be missing—what you see is all there is (WYSIATI), as Kahneman puts it. That’s why change leaders and communicators must design messages that anticipate human filters and work with them, not against them.

The Return to The Office Dilemma

Imagine a company board announces that it is ending hybrid work. From next quarter, all staff are expected back in the office full-time, because the board believes that this will improve productivity and ultimately increase bonus pools.

Employees are always supportive of increased bonus pools, but such a disruption to their daily routine is likely to see many react with frustration. Since home working was embedded during COVID, many have come to value the flexibility and the better work-life balance it provides. It is thus understandable that they will feel blindsided and not be happy about it.

So, how should leadership communicate an important organisational change such as this?

Here is a possible 8-Step-by-Step Communication Strategy aligned to Kotter's Model

Create Urgency: At this initial stage, that could mean sharing verified data showing remote work challenges, such as missed innovation, reduced rapport amongst colleagues, and weakening culture.

Build a Coalition: To build a change coalition that could involve talking and listening to the concerns of respected team leads early and co-creating possible solutions, such as a phased return to the office, to give colleagues enough time to adjust their daily routines and commitments.

Develop a Vision: At this point, clearly articulating the benefits of in-office collaboration for staff, rather than just the expected productivity gains for the business, could accelerate buy-in. Increased bonuses are good, but for many, work-life balance carries just as much weight, if not more.

Communicate the Vision: At the early stage, when one-way communication is appropriate to sell the vision to staff, the AIDA (Attention, Interest, Desire, Action) marketing model can be a useful tool in support of behavioural change.

Here’s how it could be applied:

Attention: Communicate a compelling story or data point in support of the change, such as a key industry insight that is not widely known.

Interest: Share how the change ties to the purpose and shared success of the staff.

Desire: Outline employee benefits (career development, team energy, higher bonuses). The emphasis here is on what can be gained as opposed to what is being taken away.

Action: Communicate clearly in an appropriate forum on the next steps and the feedback channels available.

Empower Action: Listen to feedback and let teams design their return approach within the necessary guidelines.

Generate Short-Term Wins: Celebrate quick successes as a group, such as team projects that are now thriving in the office.

Sustain Acceleration: Reinforce culture-building wins with continuous communication across the business using different communication channels that best support the message.

Anchor in Culture: Communication is necessary for rapport and engagement. Build rituals and spaces that make office work desirable as a place to interact with each other. Ideally, staff should be motivated to come to the office so that they can catch up in person with their colleagues on a human and professional level.

While leadership sets the direction of change, staff also play a vital role in shaping how change unfolds. Employees can engage proactively by seeking clarity, offering constructive feedback, supporting colleagues through uncertainty, and participating in co-creating new ways of working. Active involvement will not only help adapt more effectively, but it will also ensure that the change envisioned also reflects the realities and needs of those it is going to affect most.

Crucially, this plan must integrate managerial and leadership communication, so it is important to think through the appropriate communication channels.

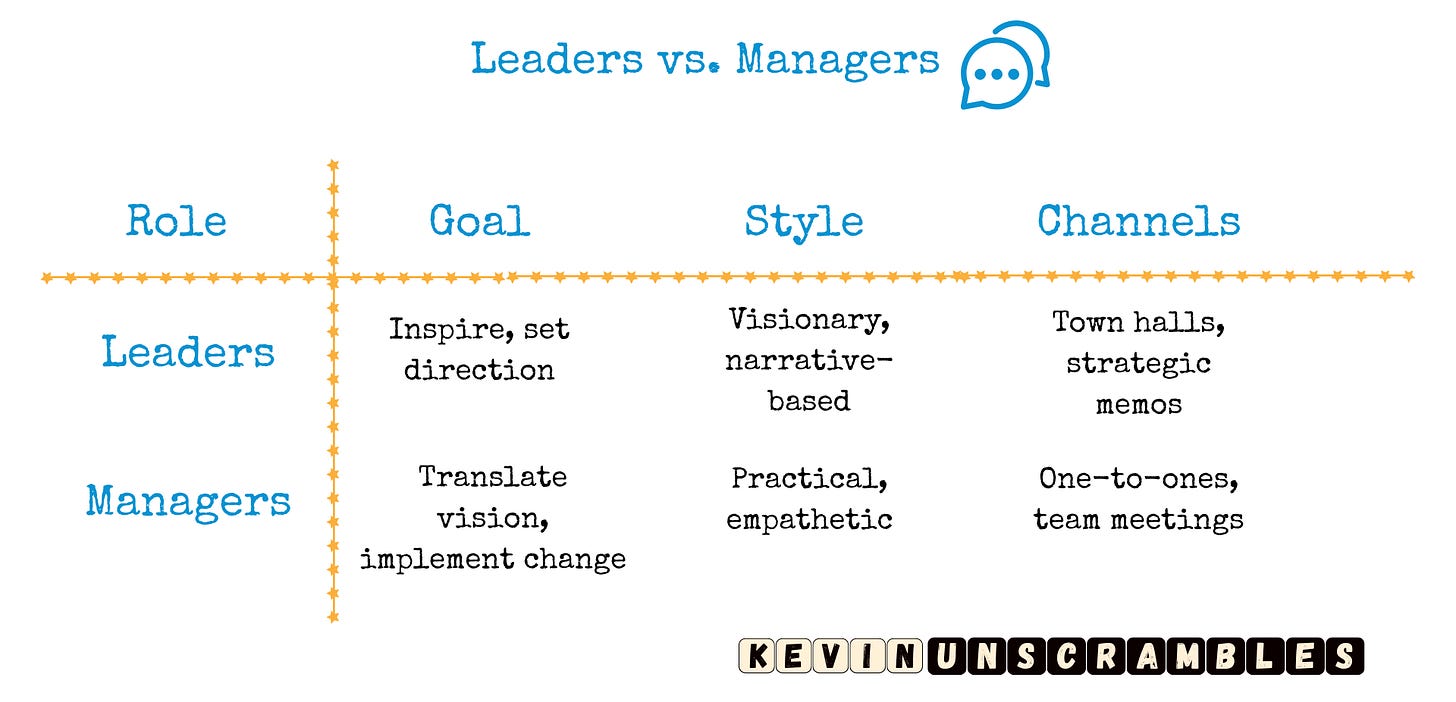

While leaders frame why, managers enable the how. Misalignment here creates confusion and disengagement. I have seen the confusion that is created when these two get mixed up – managers creating their own unique vision and leaders getting bogged down with the small details. So, during transformation, this distinction becomes vital.

A Systems Lens: Communication as a Feedback Loop

From a systems perspective, communication isn’t linear. It’s a feedback loop. Poor communication creates reinforcing loops of rumour, resistance, and retreat. Meanwhile, good communication builds positive cycles of learning, adjustment, and alignment.

To ensure communication remains effective throughout the change process, leaders can employ measurement tools such as surveys, pulse checks, and ongoing feedback loops. These provide valuable data on how messages are received and understood, so that timely adjustments can be made to keep the intended transformation on track.

For example, if early employee feedback on office return logistics is ignored, discontent and staff retention rates will spiral. But if it’s heard and addressed, it builds trust and reduces pushback. It can also save the business a lot of time and money in new recruitment drives.

Companies, just like societies, are complex adaptive systems, and sense-making must be distributed. A decentralised approach to understanding and responding to changes and challenges is what works best. Good communication makes the invisible visible, it lets the system “see itself,” and thus it can then adapt and evolve.

Change Successfully Communicated is Change Made Possible

Good communication alone doesn’t guarantee success, but without it, the likelihood of failure rises dramatically.

So, whether we are changing work models, reimagining strategy, or transforming policy, communication must be more than transmission—it must be engagement, dialogue, and a system of meaning-making.

Leaders who get this and truly understand the minds they’re speaking to, the biases they must gently overcome, and the structures through which people connect can successfully turn initial resistance into participation and then change into transformation.

In the end, communication is not an optional soft skill that we can afford to play lip service to. It’s the core skill that makes all change possible.