The Power Playbook: The Three Faces of Power

Why there's more to power than what’s on the formal org chart

In most companies, we’re often led to believe that the org chart tells us everything we need to know—who reports to whom, who approves what, who signs the cheques. But anyone who’s spent time inside a real business organisation knows that’s only part of the picture.

Big decisions don’t always follow formal structures. Strategies stall, initiatives quietly fade out, and people with no official title somehow manage to steer the ship. So what’s going on?

Well, the real world is a bit more nuanced: power isn’t just about structure. It’s also about strategy, perception, and silence.

This is exactly what British political scientist Steven Lukes uncovered in his classic “three dimensions of power” model. He wasn’t thinking about corporations when he developed it, but political science and business often blend into each other, especially when it comes to change, conflict, or transformation. And if we’re grappling with resistance or internal complexity, Lukes gives us a sharp lens for understanding how power actually operates.

The Political Science Model

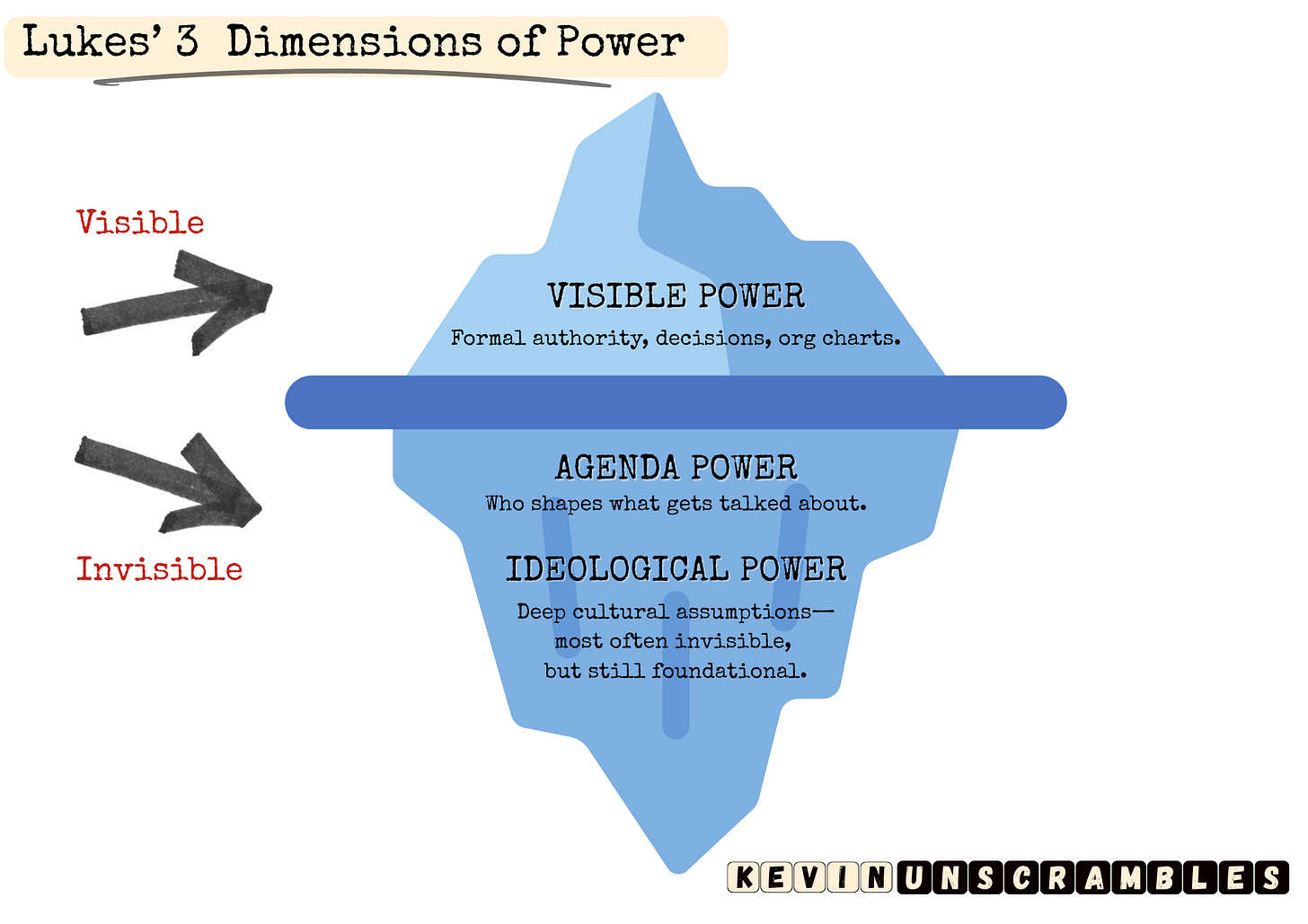

Lukes’ Three Dimensions of Power challenged the old idea that power only has one face—that it is only about who wins a debate or a vote. That’s just the surface. Below that are two deeper, subtler layers of influence—what gets discussed, what doesn’t, and what people believe is even possible.

Here is how the model works:

Different approaches have been used to illustrate the model graphically, such as a pyramid and concentric circles with visible power in the centre. However, I think the iceberg approach works really well in illustrating the power that is visible and invisible above and below the surface.

Visible Power (overt power)

Who prevails in a formal decision or vote?

For example, a budget signed off, a key leader appointed, or the approval of a new strategy.

Agenda Power (the mobilisation of bias)

Who decides what even makes it onto the table?

For example, you may have a transformative proposal, but if you can’t get it on the agenda, it's not going to happen.

Ideological Power (deep cultural assumptions or unspoken norms)

Who shapes what people believe is possible, normal, or acceptable?

For example, cultures that make dissent feel disloyal, or status quo assumptions that never get questioned. In the corporate world, this can include internal branding, mythologies about “what makes us successful,” or unspoken taboos that shut down dissent.

This model shows that power isn’t just about outcomes; it’s also about the battles that never get fought.

Why This Matters for Business

This might sound theoretical, but once you see it, you really can’t unsee it.

In today’s organisations, all three faces of power show up in strategic and subtle ways:

Visible power sits with formal leadership—executives, budget holders, and boards. Clear, necessary, and trackable—but often reactive.

Agenda power lives with gatekeepers—chiefs of staff, respected insiders, project leads. These are the people who shape what gets attention.

Ideological power is embedded in culture, language, and mythologies. It’s why some companies can’t pivot—even when the writing’s on the wall.

Take a stalled transformation effort. On paper, everyone’s aligned. But behind the scenes? Middle managers keep “raising concerns,” or there’s quiet discomfort with the direction of change. That’s agenda and ideological power doing their work.

In moments of disruption or internal conflict, this model helps unscramble why plans fall apart: because formal authority alone wasn’t enough to overcome the other two dimensions of power.

How Some Teams Are Adapting the Model

Here’s how some forward-looking organisations are beginning to apply Lukes’ model explicitly:

Stakeholder mapping tools help leaders track both formal and informal influence—who people listen to, trust, and follow.

Agenda-setting rituals such as reverse town halls or open-priority weeks create space for ideas to surface from outside the usual centres of control.

Culture audits, internal storytelling campaigns, and norm-resetting initiatives help loosen the grip of ideological power—challenging what’s seen as acceptable or possible.

These are practical ways to rebalance influence. And they reflect a growing awareness that managing power means managing systems.

Power is Not Just Positional

Yes, titles still matter. But they’re only one piece of the power puzzle.

If we want to drive real change, we must read between the lines: watch for what’s not being said, notice who’s shaping the agenda, and challenge the assumptions holding the system in place.

Lukes’ model isn’t just political theory. It’s a toolkit for leading through complexity, navigating resistance, and unlocking transformation.

And the truth be told, that’s the world most of us are working in.