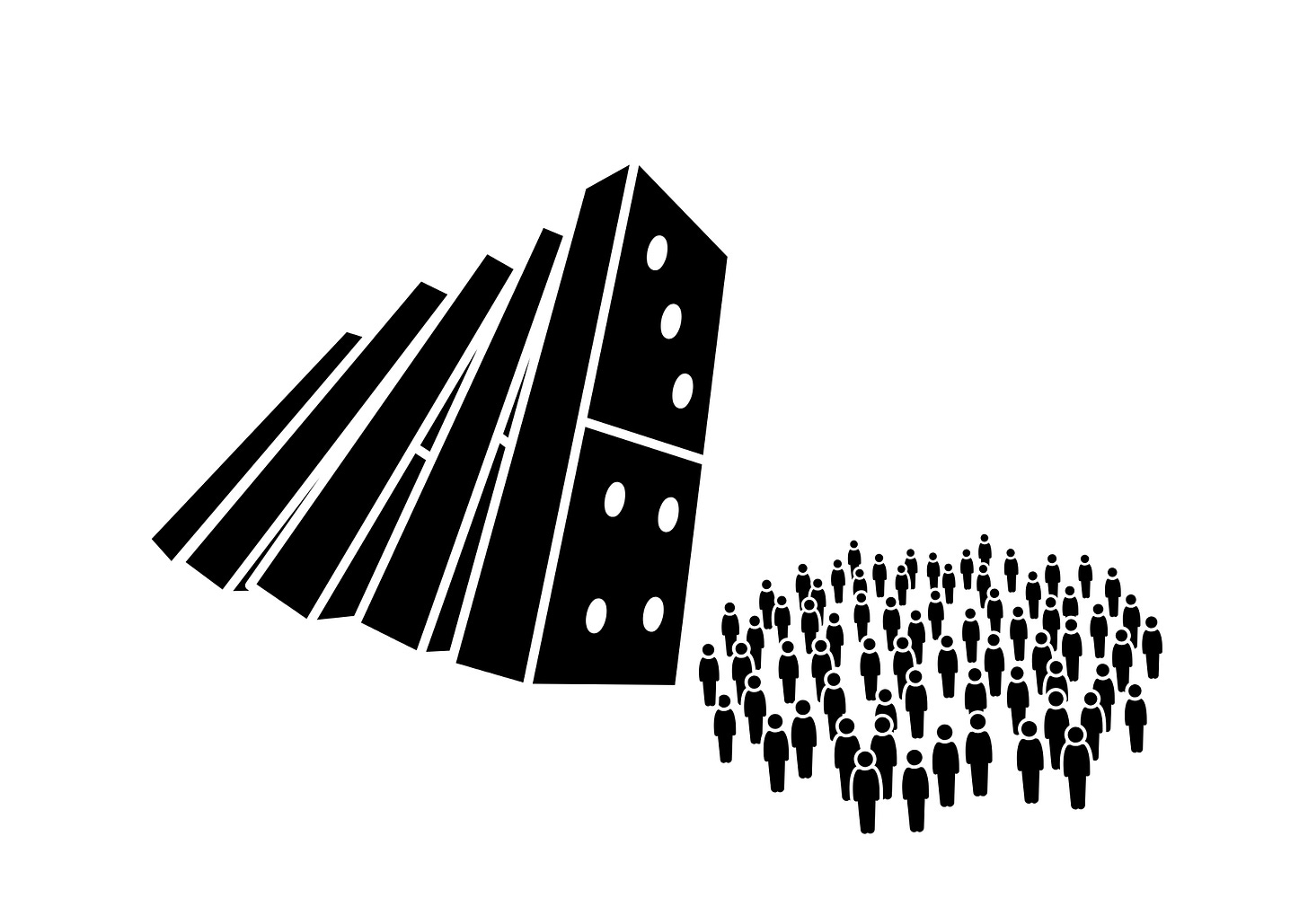

The Uneven Shape of Change

Why a handful of companies dominate markets and a few nations can reshape the international system

Most of us are taught to think in averages. Average cost. Average returns. Average customers. Average outcomes. We’re told that being above average is “good enough.” And when we think about things such as economic development, business, or progress, we often frame it through that same lens.

But averages can be misleading. Imagine an aid…