Venezuela is the Latest Example of a Global Drift Toward Authoritarianism

Election results in Venezuela are just the latest example of the broader trend of democratic backsliding

The contested results from last week’s election results in Venezuela are just the latest example of the broader trend of democratic backsliding and the drift towards authoritarianism throughout the democratic world.

What just happened in Venezuela?

Last weekend millions of Venezuelan voters went to the polls in a presidential election widely seen as the most crucial election since the incumbent President Nicolás Maduro took office 11 years ago. Opinion polls had suggested that Maduro was well behind and unlikely to win a third term. One poll conducted last month found that Maduro was behind by more than 20% and that a widespread desire for change had emerged among voters.

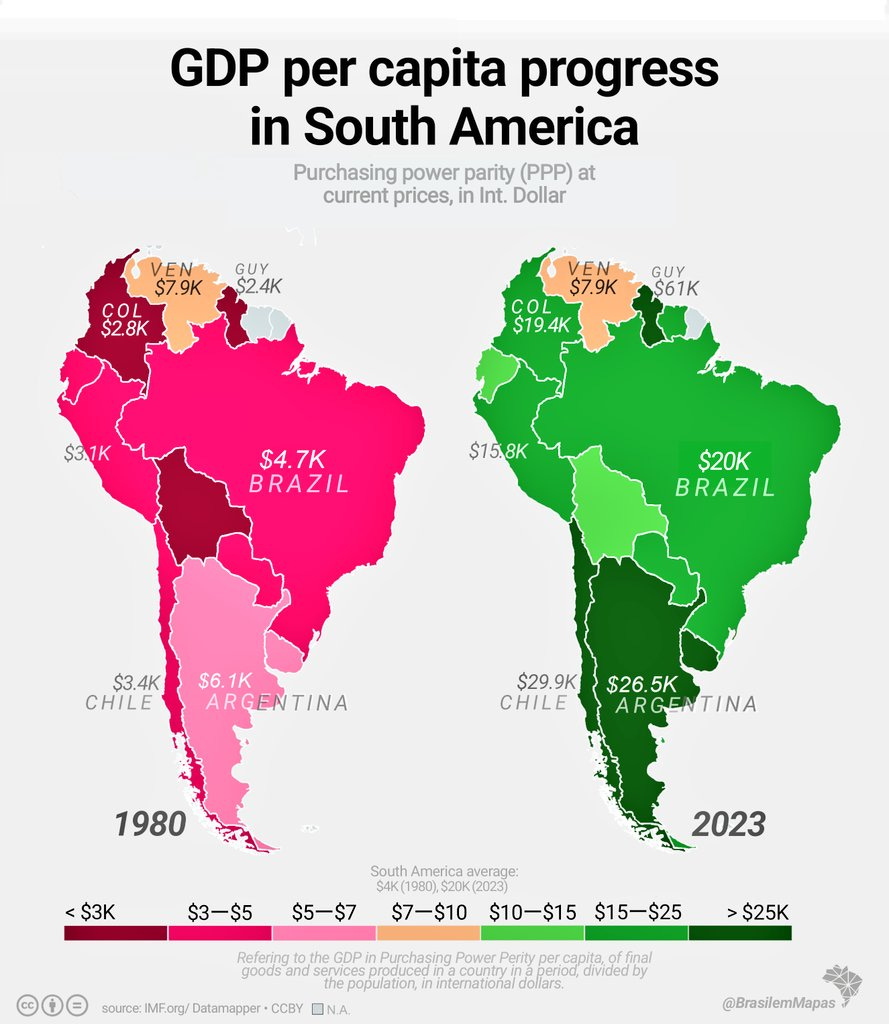

Maduro was unlikely to serve for another six years and was about to be thrown out of office by voters given his incompetence and mismanagement of this South American petrostate which has seen the dismantling of democratic institutions and economic collapse. Freedom House, a non-profit organisation that tracks threats to democracy and freedom globally, has assessed the country as not free, assigning it a score of just 15 out of a possible 100. The authorities in Venezuela have cracked down on opposition parties, prosecuted opponents without due process, restricted civil liberties, and seized full control of state institutions. The country has faced hyperinflation, widespread poverty, and significant humanitarian challenges. With little economic progress, it has become the sick man of South America.

Venezuela has now endured more than two decades of Bolivarian Socialist government, started by Maduro’s successor and mentor, Hugo Chavez. It has not delivered. The country has gone from one of the richest in South America to one of the poorest. It has gone from the promise of inclusive democracy to one now better defined as authoritarian. Close to eight million Venezuelans have emigrated from the country for a better life elsewhere. Those who stayed saw Sunday’s election as their chance to use their vote to turn the page and finally bring about the change they hoped for, by electing the opposition candidate, Edmundo González Urrutia.

However, that has not happened. The Venezuela electoral council president, Elvis Amoroso, a Maduro loyalist, had declared Maduro the winner with 51.2% of the votes compared to 44.2%, with 80% of the votes counted. However, that announcement came amid reports of irregularities in the counting of votes and voter intimidation. The opposition has disputed the results saying the result was impossible, raising concerns that this election was stolen. So far, insufficient proof has been provided by the electoral council that would substantiate their claim that Maduro had won.

At issue, are discrepancies between machine vote records and their paper counterparts, which have not been made available by the electoral council, and which would help verify if the machine vote records are correct. An exit poll had projected a resounding victory for Edmundo González Urrutia with 65% of the vote compared to just 31% for Maduro. The leader of the opposition, María Corina Machado, said in a post on social media this week that it was Edmundo González Urrutia who had won, directing voters to a website that suggests as much. The voting record information that is available to the opposition suggests that González Urrutia got 67% of the vote compared to 30% for Maduro.

If Maduro had won, then there would be no logical reason why full voting records should be withheld from public scrutiny given that transparency could prove his credibility.

Edmundo González Urrutia also took to social media this week asking “Venezuelans to continue in peace demanding that the result be respected and the records be published.”

This week’s disputed election in Venezuela is not the first time that questions have been raised about the legitimacy of the result. The last presidential election in the country, held in 2018, saw Maduro return with an easy victory, but that victory was helped by election irregularities.

In the run-up to that election potential opposition candidates were either jailed or prohibited from competing, and the electoral system was manipulated in his favour. The 2018 election was widely considered a farce by many of the country’s neighbours. At the time, sixteen nations in the region issued a statement calling for free and fair elections, the return of democracy, and respect for human rights in the country.

Not much seems to have changed. In the run-up to the 2024 election, Human Rights Watch, a non-profit human rights advocacy, wrote that “the electoral process has been marred by human rights violations and irregularities that have kept the playing field uneven.” In May, the electoral council took a unilateral decision to withdraw its invitation to the European Union to observe the election.

Moreover, the reason Edmundo González Urrutia was the opposition’s candidate in 2024 was that the leader of the opposition, María Corina Machado, was barred from running. Last weekend's election irregularities in Venezuela and the deadly crackdown now unfolding on the streets of the country this week are just the latest example of a broader global trend of democratic backsliding as undemocratic leaders seek to cling to power.