Untangling the Difference Between Populism and Nationalism and Why It Matters

One is compatible with liberal democracy, the other just feeds off it.

Populism and nationalism are two words that are heard and seen more often in our politics, in the media, and online. They are often used interchangeably and are most often used in a pejorative manner. There is an impression that both populists and nationalists are, well, cut from the same discriminating cloth.

To label a politician as a populist or a nationalist usually means passing judgment that they are some sort of a liberal outcast, that they don’t have the greater good in mind.

In some respects, this is true, populists and certain types of nationalists have wreaked havoc on their populations. There are lots of examples from recent history that prove this point. Similarly, loyal followers of some of today’s populist politicians often seem more like something out of a doomsday cult collective than concerned citizens seeking to improve their democracy. However, populism and nationalism are not the same phenomenon. They have different dynamics.

As the Western world looks increasingly likely in the coming years to pivot away in some shape or form from the hard-core globalism of the last few decades, an era where it seemed that the nation-state had become redundant, it is worth untangling these two concepts so that we can then make more rational choices about whom we vote for, why we vote for them, and what kind of political futures we want for our communities.

This is particularly the case given that nationalism is often understood as the opposite of globalism and that our politics are now increasingly focused on what is going on at home. If we must have less globalism and thus presumably more nationalism then we should really know some more about what we are likely to be dealing with so that we can shape our political communities for the better and make sure that it is of the welcoming and inclusive kind.

The same is true with populism. The rise of populism is often seen as a response to the perceived negative consequences of globalization. The globalization of the last few decades is really the product of the ideology we have used to run our liberal democracies, but in that same period, globalization seems to have progressively lost its fizz with large parts of the Western electorate.

For many, globalization has become more associated with taking money out of our pocket than putting money in it, particularly as many industrial jobs have been outsourced overseas and more people without a college degree have ended up working in low-paid service jobs out of necessity rather than choice.

Populism has grown out of frustration with these sorts of outcomes and more recently, and more worryingly, has also become blended with a more malignant form of exclusionary nationalism often called national populism. The last decade has certainly not been liberal democracies’ finest hours.

Moreover, the combined dark forces of populism and exclusionary nationalism are still in vogue and could be on the cusp of a resurgence. In the United States the former president, Donald Trump, has recently gotten the band back together and looks set to rerelease the America First anthem to play in venues all across America between now and election day in November 2024.

How to spot a populist

To start our journey of trying to untangle these two concepts let’s start first with the task of trying to spot who could be considered a populist.

From the research I have done, I think the populist politician is in many ways a sort of artist, the extroverted type who seeks to gain a large following by being the most popular, by playing to the popular demands and emotions of the crowd. The crowd requests the hits and the rockstar populist sings them out loud. The lyrics of the song are designed to stir the emotions of the people. With strong lyrics, the crowd’s response can be euphoric.

Many populists are great communicators. Some had previous careers as television stars or even as comedians. They often have no experience in government or even politics. This, however, doesn’t really matter so much because what they can do really well is to be really entertaining in an arena where politics is often considered dull. Many populist politicians have created the illusion that their vision is better than anything that has come before and moreover, they also seem to have perfected the skill of lying with a straight face to keep their audience engaged.

Cable news normally likes giving airtime to such types because they can create controversy which helps drive up their ratings. There is no such thing as bad publicity in this game. Good communication will always trump good policy proposals for the populist because the primary strategy is to suck up all of the political oxygen and become the most popular with voters in order to gain political power. The rest doesn’t seem to really matter that much. The game is to be popular in the pursuit of power. That’s it.

Just think back to your school days and the matter of electing a student to the post of student representative or school president. A popular student looking to get elected in this setting might advocate for something like the abolition of homework assignments or regular tests. This could prove quite popular with many students who are frustrated with the burdens of school life.

Such a move can get the vote out and deliver the budding young populist to an early position of relative power. The problem though is that if such a revolutionary homework policy was ever implemented it would also likely reduce the quality of the education received and student exam scores. This is because as most of us already know if you want to succeed, you’ve got to do the work. Sometimes doing what you want just doesn’t provide you with what you need. In politics, the same principle applies, but for some who have hitched themselves to the populist wagon in recent years, this principle has been overlooked.

We are just over two decades into this new century and so far the populism technique has had an increasing impact on the world’s democracies from places as geographically varied as Hungary, Poland, Brazil, and the Philippines.

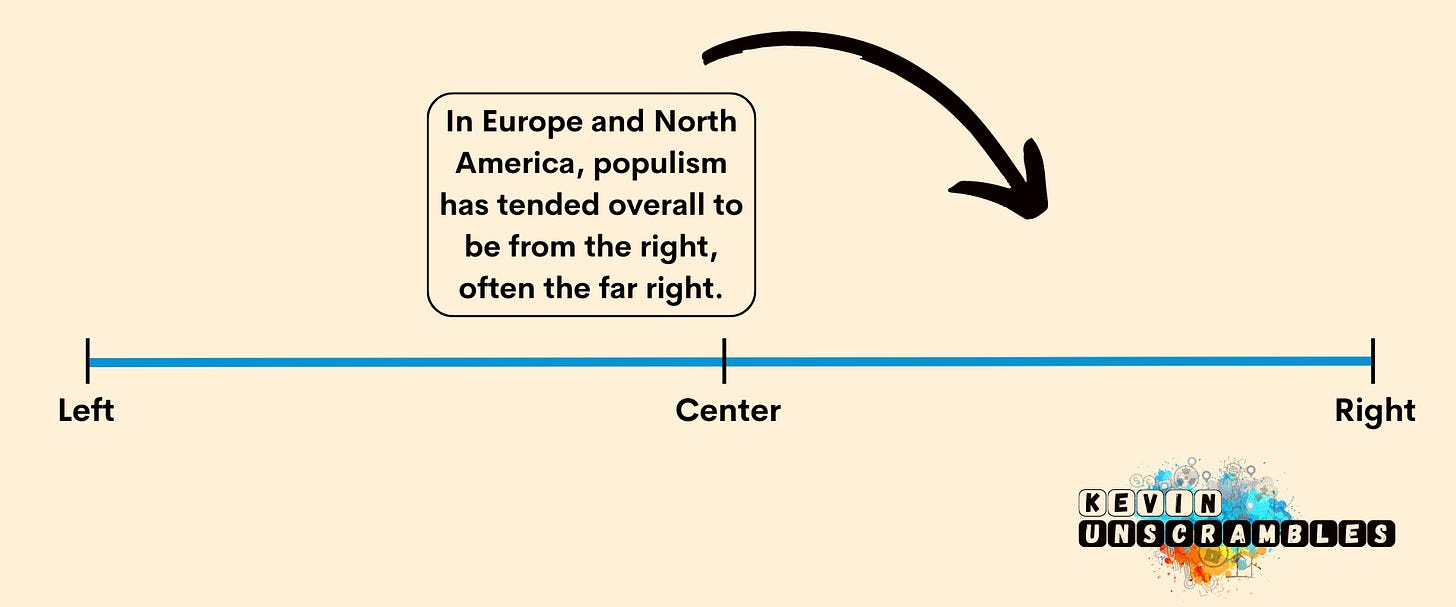

Populism can be driven or provoked by either the political left or the right, however, in Europe and North America, it has tended overall to be from the right, often the far right, making it more compatible with policies that argue against immigration and argue for traditional values. Populist politicians such as Trump in the U.S. or the Euroskeptic Brexiteers in the UK have had success and have managed to capture political power.